Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

-

Welcome to The Platinum Board! We are a Nebraska Cornhuskers news source and community. Please click "Log In" or "Register" above to gain access to the forums.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

2023-24 Portal Szn

- Thread starter Seaofred92

- Start date

Sometimes in high leverage negotiations you gotta walk away to get the other side to pay more

Quarterback recruiting in the transfer portal era: 'A constant chess game'

Development at the sport's most important position is often taking a back seat as coaches and players seek instant gratification,

By Antonio Morales

Dan Sayin describes his youngest son as “a planner.”

So when Julian Sayin — the No. 1 quarterback in the 2024 recruiting cycle — signed with Alabama, there was some thought about Nick Saban’s potential retirement. Maybe after his next national championship. Maybe sooner.

It turned out to be much sooner — the day Julian, an early enrollee, started classes for Alabama’s spring term.

“It was a shocker,” Dan Sayin said.

Julian was enjoying his time at Alabama and had already grown close to starting quarterback Jalen Milroe. But with Saban’s retirement, the family started to consider other options.

“A lot of ‘What if we went into the portal?’” said Karen Brandenburg, Julian’s mom. “A lot of ‘What are good options in my head? What did I like before? What looks good now?’ … And also, of course, ‘What if I stayed?’ He loved the QB room at Alabama. But you know, it just wasn’t the same. He had come to play for (Saban).”

A new reality hit the Sayin family, just like it has for many before them: Quarterbacks plan, college football laughs.

As the sport’s landscape rapidly changes — most notably from a transfer portal that incentivizes impatience from all parties but also due to the coaching carousel and NIL — there’s more uncertainty than ever at the quarterback position.

Development often takes a back seat as coaches and players seek instant gratification, and mapping out the future for the position at a school — on both ends of the college football food chain — is nearly impossible.

“It’s like this constant chess game with everybody trying to figure out what’s the next move and what’s going to be best for everyone,” USC coach Lincoln Riley said. “You certainly have to be prepared for anything and everything.”

Riley is viewed as college football’s preeminent quarterback developer. He coached Baker Mayfield, Kyler Murray and Caleb Williams to Heisman Trophies. Mayfield and Murray were both No. 1 picks in the NFL Draft, and Williams is expected to join that prestigious list next month.

So how does he feel about the state of quarterback development nowadays?

“Ohhhhh, man,” he said. “It’s probably not as healthy in the last several years with all the recent developments.”

Many will interpret “recent developments” and point to NIL, but coaches and families will tell you the transfer portal has had the greater impact. The quarterback position, first and foremost, is all about opportunity.

And Year 2 on campus seems to be a major inflection point for highly touted quarterback prospects. Eight of the top 15 quarterback recruits in the 2022 cycle have already transferred before their third college season

Danny Hernandez is a private QB coach who has trained Sayin, Bryce Young, Malachi Nelson and Maalik Murphy, among others. He’s seen quarterback recruiting and development from every angle.

“I don’t think we’re ever going to see another Mac Jones,” Hernandez said. “I know after two years if you’re in the mix or not.”

Jones, a four-star prospect coming out of high school, waited three years — behind Jalen Hurts and Tua Tagovailoa — before he earned the starting job at Alabama in 2020. In his only season as the starter, Jones earned consensus All-America honors and led the Crimson Tide to a national championship.

There are some exceptions — Carson Beck at Georgia is a prominent example — but stories about patience and development have become rare in the era of immediate transfer eligibility.

Only about a dozen of the 68 Power 4 teams are projected to start quarterbacks in 2024 who waited multiple seasons before ascending to the top of the depth chart. On the flip side, as many as 42 power-conference teams could start a transfer quarterback.

Quarterbacks and their families are typically portrayed as the source of impatience, but coaches are expediting the process by recruiting over their incumbent players in the search for a quick fix with a known commodity.

“You’ve given both these coaches and players another tactic to use and both are. I think there’s a lot of impatience,” Riley said. “Some of that comes from, at times, unrealistic expectations of those that aren’t within the walls where people feel like they just have to do something drastic to meet those expectations.

“But I understand the temptation behind it, especially with that position. There’s so many options and possibilities out there now, I think for everybody, sometimes it’s hard not to take a look across the fence and wonder if it’s better on the other side.”

Alabama and Ohio State entered last season as national championship contenders despite having questions at quarterback. And it was a bumpy ride at times for a pair of teams that had grown accustomed to stellar quarterback play. It’s difficult to envision these programs — and others with legitimate national title aspirations — putting themselves in that sort of situation again unless they are extremely confident about the talent on hand.

Every program seemingly wants the uber-talented youngster or the experienced transfer. The middle-class quarterbacks, who sign with a school and wait for a few years, are dwindling. Other aspects factor into this, too. The players with that extra year of eligibility due to the pandemic are staying in college and blocking the path of other potential starters, and colleges are taking fewer chances on the late-blooming high school quarterbacks because they know they’ll have options in the portal come December.

“Unless it’s a five-star, he-can-play-right-away type of talent or sit for a fall and be ready to go the next year, how many of (the top programs) really are gonna be able to take and develop guys that might be multi-year, longer term, long-range, high-ceiling prospects versus living in the portal?” Elite 11 president Brian Stumpf said. “They’re not gonna really be able to have that five- or six-game trial and error period anymore.”

Time will tell what sort of impact all of this player movement will have on college football’s ability to develop quarterbacks for the NFL. There is plenty of optimism about the crop of QBs who will be drafted later this month, but there’s already pessimism about next year’s class. Is that just a blip on the radar or a sign of things to come?

Quarterback plans have always been tenuous at best.

JT Daniels was supposed to be USC’s starting quarterback for three seasons before heading off to the NFL and being succeeded by Young. Daniels started his freshman season for the Trojans, tore his ACL in the season opener of his sophomore year, and never played for USC again. Young flipped three weeks later and eventually won a Heisman Trophy at Alabama.

Trying to build out a plan at quarterback beyond a year is practically impossible.

Maybe you stagger quarterback commitments every other year and hope the younger one doesn’t leave if he loses a competition. Maybe you take a quarterback every year — but that seems like you’re guaranteeing you’ll lose someone.

“At the end of the day, you don’t know who exactly is going to be in there,” Riley said. “There’s never that sense of, ‘Alright, well we’ve kind’ve got our room set.’ You just never know.”

The only thing a coach can do is make no promises.

“I think you can (keep a quarterback for a few years) if you recruit the right guy, you don’t trick him, you’re just honest with him and you explain the way it is,” Arizona State coach Kenny Dillingham said. “Is it a guarantee that happens? No. There’s no guarantee it’s going to go how either of y’all think it’s going to go. That’s the crazy part about it. Nobody truly knows how it’s going to play out.

“The only promise you make is you’re going to do whatever you can to make them successful and if it works out then great, and if it doesn’t then you’ve got to respect that.”

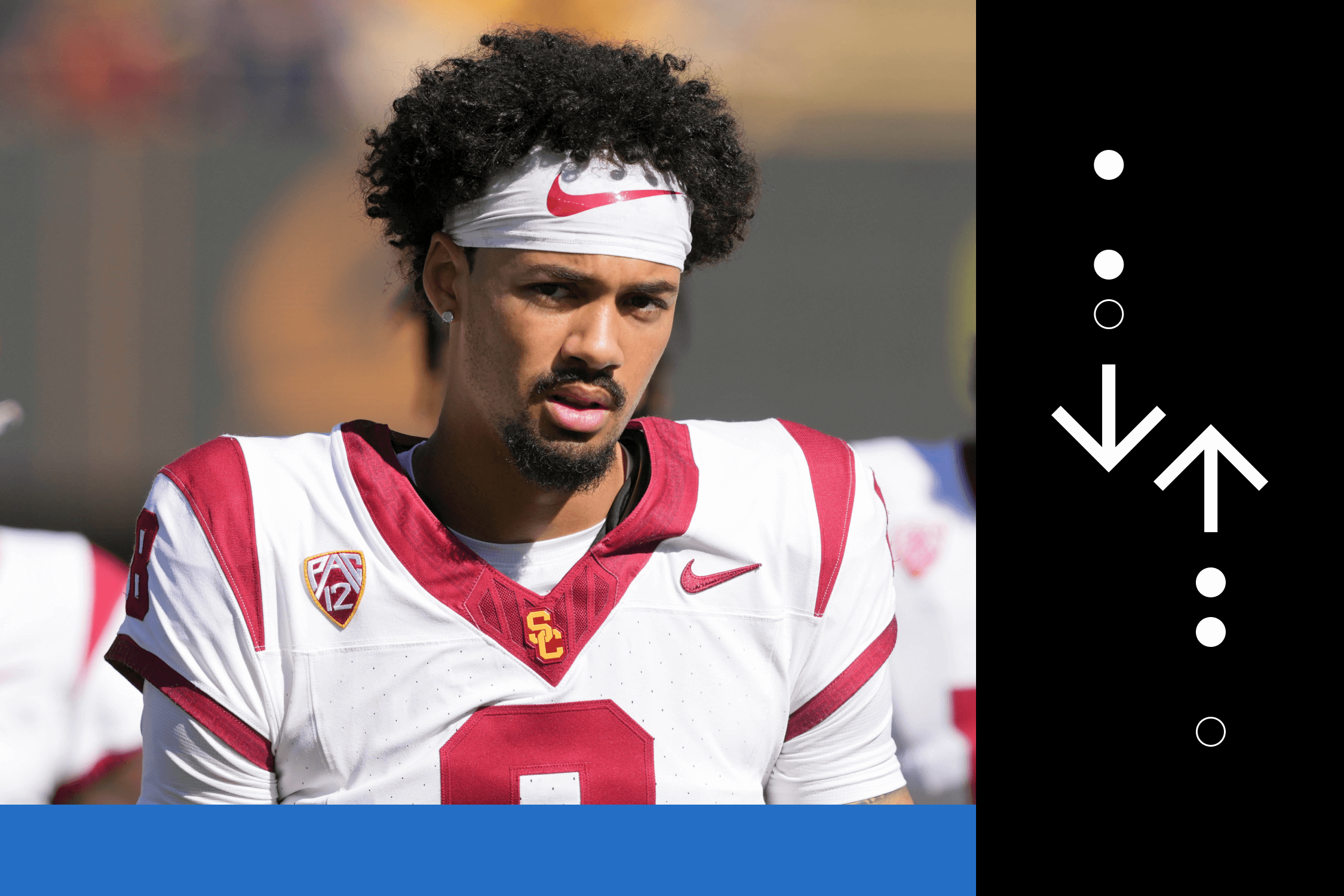

Riley said that’s placed more of an emphasis on finding quarterbacks who are willing to be patient when things don’t go their way early in their careers — someone like Miller Moss at USC.

Moss, a top-100 national recruit in the Class of 2021, enrolled at USC with Jaxson Dart. He stayed when Williams arrived, and he beat out Nelson, a five-star freshman, for the backup job last season. Now entering his fourth season, Moss is poised to be the Trojans’ starter.

Moss could join Beck at Georgia and Garrett Nussmeier at LSU as starting quarterbacks at prominent programs who sat on the bench for multiple seasons. Moss and Nussmeier stayed despite changes at head coach at their respective programs.

And it’s this frequent movement on the coaching carousel that contributes to the upheaval. When Riley left Oklahoma, the quarterbacks fled. When Jonathan Smith bolted Oregon State for Michigan State, two talented quarterbacks (Aidan Chiles and DJ Uiagalelei) left the program and found new homes.

“You can’t even count on the coaches you’re being recruited by,” Sayin’s mother, Karen, said. “I don’t even know in the future. I think it’s going to get harder and harder.”

Sayin had a plan once Saban announced his retirement. He had strongly considered Ohio State out of high school and was very familiar with the Buckeyes’ new offensive coordinator, Bill O’Brien — who held the same position at Alabama when he committed to the Crimson Tide in November 2022.

So Sayin opted to enroll at Ohio State even though the Buckeyes had another five-star quarterback in their 2024 recruiting class, Air Noland, and even though O’Brien made it clear he might pursue a head coaching opportunity.

“Granted Air was at Ohio State, but he (Julian) really had to just look out for himself,” Karen Sayin said. “It was a business decision and it was like, ‘Where can I get developed? I think I can compete anywhere.’”

And guess who will not be his offensive coordinator at Ohio State? O’Brien was named head coach at Boston College two and a half weeks after Sayin committed to the Buckeyes.

There’s a musical chairs element to the transfer portal. There are only so many destinations that are going to check all the boxes, and the longer a quarterback waits to make a move, the fewer spots will be available.

“You’re going to put yourself in a position where you’re like, ‘Geez, Ohio State’s not available anymore. Nebraska’s not available anymore. Michigan’s not available anymore,’” Hernandez said. “Guess what? These Group of 5 schools now are going to end up benefiting from that.”

That statement backs up Dillingham’s theory that “there’s going to be more talented quarterbacks playing in college football than there’s ever been.”

In other words: Quarterbacks want to play.

Nelson was a five-star prospect in the 2023 recruiting cycle who would have been a take for almost every FBS program. But after USC flirted with former Kansas State quarterback Will Howard in the December portal window, Nelson opted to transfer after one season with the Trojans.

The market, for various reasons, wasn’t as robust as many expected, and Nelson eventually landed at Boise State. Meanwhile, experienced quarterbacks who played at the FCS level (such as New Hampshire’s Max Brosmer) or for a G5 program (Toledo’s DeQuan Finn) ended up at Minnesota and Baylor, respectively, and are in line to start for power-conference programs.

The market spoke, and an experienced option — at least at the highest levels of the sport — is valued more than someone who might have been talented in high school but hasn’t proven it in college.

“That other guy … He’s done it with the live bullets whizzing by,” Hernandez said. “So he has that film. Why wouldn’t (a program) go that route?”

It’s tough for the Group of 5 programs that develop these quarterbacks only to lose them to high-profile schools.

And while there will be more quarterbacks like Nelson and Ty Thompson, a top-50 recruit in the 2021 cycle who waited three years at Oregon before transferring to Tulane, who end up at G5s, those schools will have to deal with the fact that many prospects view them as an elevated level of junior college football — play well, get your tape and then transfer to a bigger school.

“That’s exactly what it is,” said one FBS head coach who spent some time at the G5 level recently. “You have guys looking at that as a business decision. What’s most important is playing young so you can get big money while you’re still in school. If you don’t get huge money coming in the front door or if you’re not the guy early wherever you are, then you have to shift and, ‘OK, where can I go play right now?’”

Some programs will likely embrace that and make it part of their pitch. There might be some culture issues and a constant churn to navigate, but the appeal is certainly there.

It’s one more dynamic in a world that — as the sport changes — is taking on a much different look.

“Whether you’re talking about the portal or performance — a lot of it comes down to the belief in themselves and just their inner confidence that they believe when that opportunity presents itself that they’re good enough to go seize it,” Riley said. “I think this process in some ways reveals that maybe even more than before.”

— Grace Raynor contributed to this story.

As if he gives a single fuck about a natty after leaving a playing time role at Georgia in the first place lol. If UAB threw him the bag his ass would be on the next flight to Birmingham.

He’s so N it hurts.

So damn N

So damn N

Check didn't clear or either cleared too quickly

If you believe Twitter replies there were some people posting that he had been running with the 2s mostly during spring ball at Louisville.Check didn't clear or either cleared too quickly

If you believe Twitter replies there were some people posting that he had been running with the 2s mostly during spring ball at Louisville.

Portal officially opened today right?

Lionsfan93

Wide Receiver

Recruiting Analyst

Nebrasketball

tPB OG

Happy Ending Society

- 2,677

- 2020

- 16,187

Looks like Corey Collier and Eric Fields to the portal...

Fields will end up at some G5 school in Texas and dominate. Collier may find the field at New Mexico State or somethin.Looks like Corey Collier and Eric Fields to the portal...

Today till the 30thPortal officially opened today right?

Bring him in as a W/O/NIL deal

Bring him in as a W/O/NIL deal

Probably don't even need NIL bucks to get a guy with 1 FCS tackle

Similar threads

- Replies

- 24

- Views

- 2K

- Replies

- 292

- Views

- 16K

- Replies

- 8

- Views

- 606